Stability and Balance: Letting Go of Balance to Find It

The Alexander Technique helps to improve one's balance and stability. But what is balance, and what is stability? In the process of learning the Technique, we find that many of the ideas we hold, and the goals we strive for, are contradictory or poorly thought out. If we strive for balance with an incorrect idea of what it is, we will find that our balance is actually getting worse. One might say that there are two different ideas of how to be stable and balanced: one is through fixity and holding, the other through fluidity and expansion. Often, either consciously or subconsciously, people are looking for balance through fixity. Let us start by looking at our anatomy to get a better idea of what supports us in the field of gravity.

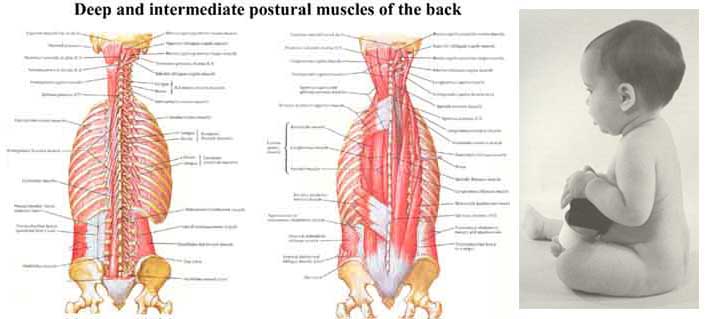

The postural muscles of the back run along both sides of the entire length of the spine, as well as right along the middle of the spine. The deepest layer are those depicted on the figure above to the left. If you rub gently along either side of your spine, you will feel a series of long muscles next to the spine - this is the surface layer of postural muscles of the back, illustrated on the figure above to the right. They should have a firm but resilient, even tone - in many people they are hard and rope-like. The postural muscles of the back function to keep our bodies upright and supported in the field of gravity. An interesting feature of these muscles is that they contain a high percentage of "slow twitch" or "non-fatigable" muscle fibers, which means that they can work all day without strain or fatigue. When they work in an integrated manner, attaching to the strong, bony structure of the spine, they provide a central lift to the body which creates a sense of lightness and ease, as pressure is taken off the joints, and fluidity and strength are maximized. If you observe the baby to the right of the anatomical drawings, you might notice both the uprightness of the baby's posture, but at the same time, the ease and lack of tension in his body. This is a result of the postural muscles working as they are designed.

However, in the process of growing up, as we imitate the tension patterns of our parents and peers, sit in front of computers, TV's, or at school, and undergo the inevitable emotional traumas of life, most of us interfere, unconsciously, with this natural, integrated support. We end up creating what is in effect a "substitute spine," a whole network of tension in the neck, shoulders, jaw, ribs, legs, etc. which replaces the natural support of the spine and spinal muscles. What people call "tension" is really the experience of this network of habitual, unconscious tension, or "substitute spine." This tension lowers our overall level of functioning, creates compression, strain, fatigue, and discomfort, and prevents fluidity and responsiveness both physically and mentally.

It is also interesting to note that "tension" involves the constant overuse of voluntary musculature, muscles that are designed only for intermittent use, and associated with our sense of "ego" (striking out, holding back, running away). So this creates an unstable background emotionally as well as physically: instead of relying on the steady, calm, natural support of the spinal muscles, we feel "stressed" and "on the alert" - our "fight or flight" system is constantly stimulated - as we must constantly "work" simply to stay upright. The Alexander Technique, by re-stimulating the deep postural muscles to work, enables us to let go of this network of tensions, regain our natural support, recover a sense of ease and poise, and raise our functioning and our performance in all our activities.

A simple illustration to highlight these two contrasting ideas of balance or stability is to think about the problems posed by riding waves on a surfboard. A surfboard rider needs extremely rapid and fluid responsiveness to remain balanced on a surfboard. This involves, as explained above, a core stability of the deep postural muscles of the back, but this core stability allows for tremendously rapid changes of peripheral musculature, and an overall fluidity of the body. The result is stability within an environment of change, and the rider remains on the surfboard (at least some of the time). People often seek stability in the opposite way, by trying to stabilize with the peripheral musculature (holding the neck, shoulders, ribs, jaw, etc.) and giving up the core, by engaging the "substitute spine" and giving up the real one. This results in falling, in instability. I think it is clear that if someone tries to stay on a surfboard by tensing up and becoming rigid, that he/she would fall off at once.

So there is stability that is inherent to our organisms when they are used according to their design, versus habitual tension, or interference with our design, which serves to prop up a fundamentally unstable core. We often mistake these holding patterns for “ourselves” because they feel secure and stable (they have developed as compensation for the lack of a core stability), and because they are so much a part of our experience that they seem “natural” and "right." Without new experiences to guide us, most people would never try to, or know how to, venture outside their learned, fixed habits of balance. Lessons in the Alexander Technique help us experience the difference between this fixed, artificial support, and our deep, fluid, natural support. This experience convinces us, on a deep level, that it is possible to let go of this "substitute spine," this contradictory effort to find balance through fixity. Gradually, as we learn to trust our innate design, our balance and fluidity improves on all levels, as we develop mental, physical, and emotional poise,