Mind Wandering and Focus

Parents and teachers are constantly telling children to "CONCENTRATE" and "PAY ATTENTION." What do these words really mean? What do you actually "do" when you decide to concentrate? Many people furrow their brows, hold their breath, stiffen their bodies, stare fixedly, or close their eyes, as if they must temporarily stop life from moving on so they can pay closer attention. Or they may fix themselves rigidly in order to notice what is going on. They may feel that they must somehow remove their mind further away to survey what is happening from a distance, to "be more objective." These effortful actions have no beneficial effects, and actually make people far less attentive. But aren't focus and concentration some of the keys to success in life? And don’t we need to make some kind of effort to focus if our mind is wandering? And why do so many people have this reaction to the idea of concentrating?

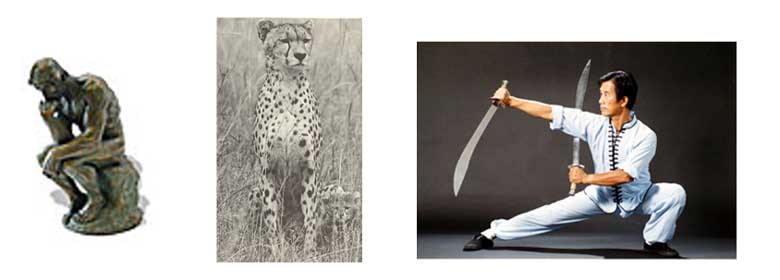

Look at the pictures at the top. On the left is Rodin’s famous statue, "The Thinker." Notice the contorted body, the strain and effort. This is a good depiction of the typical idea of "concentration." Now look at the cheetah and the martial artist: they are alert, yet open and relaxed. We are born with an open, alert quality of attentiveness; it is our biological inheritance. The strained, forced idea of concentration is an unfortunate misconception about attentiveness that we pick up from our culture as a part of our upbringing. An animal would not survive long in the wild if it engaged in what we call "concentration." It would have so little awareness of its surroundings, and would be so fixed and immobile, that it would end up as a tasty bit of prey, or a starved predator. The problem is, once we have absorbed this strained, contradictory response to the idea of paying attention, we will react this way to any attempt to pay attention. It seems that we are in an inescapable trap. Is there a way out?

By stimulating the deep engagement of the spine and its postural muscles, the Alexander Technique help us to re-awaken a more vital, biological way of being in our bodies, which includes an expanding of our awareness. We become aware of our bodies and our environment in a seamless field, and so overcome the incorrect, strained response to the idea of concentrating. We learn that the real question is not what to "do" to concentrate, but how to stop doing what causes us to narrow and fix our attention. Then attentiveness is simply there as our natural state. This is the awakening of true attentiveness. It leads to the gradual freeing from the vicious circle of false and restrictive habits of concentration that we mistakenly identify as "paying attention" or "concentrating."

Parents and teachers are constantly telling children to "CONCENTRATE" and "PAY ATTENTION." What do these words really mean? What do you actually "do" when you decide to concentrate? Many people furrow their brows, hold their breath, stiffen their bodies, stare fixedly, or close their eyes, as if they must temporarily stop life from moving on so they can pay closer attention. Or they may fix themselves rigidly in order to notice what is going on. They may feel that they must somehow remove their mind further away to survey what is happening from a distance, to "be more objective." These effortful actions have no beneficial effects, and actually make people far less attentive. But aren't focus and concentration some of the keys to success in life? And don’t we need to make some kind of effort to focus if our mind is wandering? And why do so many people have this reaction to the idea of concentrating?

Look at the pictures at the top. On the left is Rodin’s famous statue, "The Thinker." Notice the contorted body, the strain and effort. This is a good depiction of the typical idea of "concentration." Now look at the cheetah and the martial artist: they are alert, yet open and relaxed. We are born with an open, alert quality of attentiveness; it is our biological inheritance. The strained, forced idea of concentration is an unfortunate misconception about attentiveness that we pick up from our culture as a part of our upbringing. An animal would not survive long in the wild if it engaged in what we call "concentration." It would have so little awareness of its surroundings, and would be so fixed and immobile, that it would end up as a tasty bit of prey, or a starved predator. The problem is, once we have absorbed this strained, contradictory response to the idea of paying attention, we will react this way to any attempt to pay attention. It seems that we are in an inescapable trap. Is there a way out?

By stimulating the deep engagement of the spine and its postural muscles, the Alexander Technique help us to re-awaken a more vital, biological way of being in our bodies, which includes an expanding of our awareness. We become aware of our bodies and our environment in a seamless field, and so overcome the incorrect, strained response to the idea of concentrating. We learn that the real question is not what to "do" to concentrate, but how to stop doing what causes us to narrow and fix our attention. Then attentiveness is simply there as our natural state. This is the awakening of true attentiveness. It leads to the gradual freeing from the vicious circle of false and restrictive habits of concentration that we mistakenly identify as "paying attention" or "concentrating."